by Violet Cowper

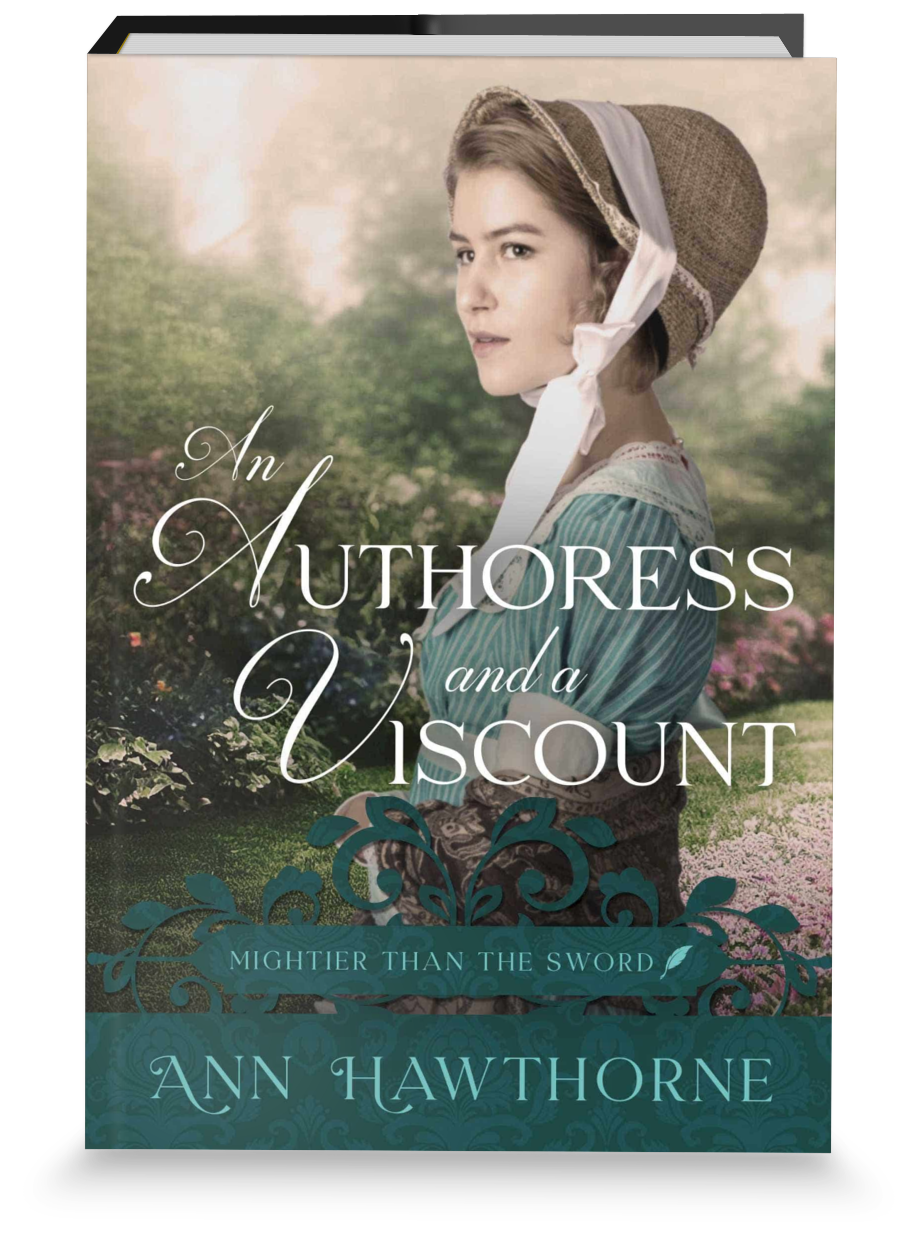

An Authoress and a Viscount

An Authoress and a Viscount

Couldn't load pickup availability

- Purchase the Paperback instantly

- It will be printed on demand and shipped to you ASAP

- Enjoy!

A heroine eager for an escape. A hero eager for a diversion. A court where no one can escape the prying eyes....

Lavinia Dudley, a young novelist catapulted into fame, has been offered a great honor—to attend Queen Charlotte. However, her new duties and the sharp-toothed social circuit drain her. Moreover, she is now at the mercy of haughty ladies who will never let her forget she is merely a music teacher's daughter.

Hugh, Lord Granville, has been offered a great opportunity—to become an equerry to the King and remedy his late father's disgrace. However, the new position tears him away from his beloved home and the life he knew, and leaves him to find escape in sensual diversions.

A royal trip to Cheltenham will throw them together. But when the scheme they concoct takes them too far, will love be enough to save them?

Main Tropes:

- Opposites attract

- Royal Court setting

- Wallflower heroine

Share

Synopsis

Synopsis

Lavinia Dudley, a young novelist catapulted into fame, has been offered a great honor - to attend Queen Charlotte. However, her new duties and the sharp-toothed social circuit drain her. Moreover, she is now at the mercy of haughty ladies who will never let her forget she is merely a music teacher's daughter.

Hugh, Lord Granville, has been offered a great opportunity - to become an equerry to the King and remedy his late father's disgrace. However, the new position tears him away from his beloved home and the life he knew, and leaves him to find escape in sensual diversions.

A royal trip to Cheltenham will throw them together. But when the scheme they concoct takes them too far, will love be enough to save them?

Intro Into Chapter 1

Intro Into Chapter 1

Lavinia wasn’t sure what exactly she expected from this year, the third year of her service at court. Part of her hoped the rules would relax and a lively quadrille would be allowed into the mix of dances. But it was as foolish a hope as wishing the sun would rise in the west one day. As far as Her Majesty was concerned, all this skipping around and twirling was most improper and certainly would not do at a ball in her honour.

Lavinia had never been to a proper ball before she came to court as the second keeper of the robes. Not even at the height of her literary fame, when she was feted by the late Dr Johnson’s own friends, did she receive such invitations. However, she was far from ignorant of the output of printers. Her publisher, Mr Wickman of St Paul’s Churchyard, made a good trade of music sheets for quadrilles and, for the more staid dancers, allemandes.

But that was outside, in the bustling world of London and Bath and Bristol and the cities beyond – in the world where life was churning like a wild sea. Here, at King George’s court, it was more akin to a mirror-smooth lake, and the dance seen most frequently at his queen’s birthday balls was the cotillion. This year, like all others, Queen Charlotte’s birthday ball was held before her birthday. Her birthday was in May; however, according to the labyrinthine logic of court ceremonies, her birthday was celebrated in January.

Lavinia drank her third glass of unsweetened champagne this evening. She was not usually partial to the drink – to any alcoholic drink – but it was hard to keep herself lively, or even lifelike, otherwise. She couldn’t imagine where the tales of court leisure and indolence came from. Perhaps, this sort of life really was going on somewhere far away beyond the orbit of her own experience. Lavinia, however, had to get up at six in the morning today – just as she had to do yesterday and every morning for the three years before that – and patiently wait to be summoned to her duties. But, of course, she couldn’t even show a hint of that kind of regimen at Queen Charlotte’s birthday ball. She knew that these were her duties, too – to smile and pretend gentle joy.

Not just to pretend, she reminded herself. To be properly good and grateful, she had to do her best to feel it in her heart. How unnatural was she that an appointment most women in the country would have committed murder for brought her nothing but dull misery?

‘This is going to be your last champagne flute for the evening,’ Mrs Juliana Schwellenberg said, her tone that of a guardian to a child as opposed to merely the first keeper of the robes to her second. ‘You have indulged yourself quite enough.’

‘I had no intention of indulging myself,’ Lavinia tried to explain in a voice as patient as it was deferential. ‘It is only that I am a little tired, and—’

‘Tired! What a fragile creature you are. One would have thought that women reared from your origins have hardier souls and bodies than this.’

Lavinia’s father was a music tutor and a scholar, and her late mother was a harp prodigy. To listen to the court ladies, one might have thought Lavinia spent her childhood tilling hard soil.

She did not correct the older woman, however. That, she knew, would lead to nothing but further acrimony. She had to do the sensible thing. She had to swallow the implied insult, pretend she was too foolish to have understood it, and nod.

Loud laughter caught her attention. She was acquainted with the men laughing – the royal equerries, from the young ones to the old ones, but she knew none of them well. They were standing apart as a small group, all tall and broad shouldered – the young men strapping, the senior courtiers having the look of military heroes. All but the man who had just finished speaking, the one whose joke caused such uproarious laughter.

He was tall; however, that was the only thing the sandy-haired gentleman had in common with them. He was lithe rather than thickly muscular and dressed in the pink of fashion to a slightly greater extent than was acceptable at the strict and sober court of King George and Queen Charlotte. His formal waistcoat of white silk was embroidered a smidgen too elaborately; his shirt, as far as Lavinia could judge from its exquisitely ruffled sleeves, was also of silk instead of linen.

Among the other men, he seemed to glow, and it was not only the matter of the candlelight reflecting upon his pale-fair hair.

‘God Almighty,’ Mrs Schwellenberg said, ‘in my day, a young man of his kind would have been called a macaroni.’

‘Why?’ Lavinia asked, not dragging her gaze away.

‘Because of the Italian foppishness, of course. Though, I suppose, these days, most fops rather emulate the French.’

What a peculiar thing the Mrs Schwellenberg’s mind must be, Lavinia mused, as must the mind of most courtiers be. Out in the streets, in the coffee houses and print shops of London, emulating the French meant alarming things that started with atheism and ended in a royal murder. Here, within the walls of St James Palace – or Kew, or, more usually, Windsor – time stood still, and the French ways still meant fashions and elaborate wigs.

The fair-haired equerry looked away from his friends and right at her. His eyes were grass green, and a smile of merriment was still on his lips. These were lips that some – Mrs Schwellenberg, for one – would have called uncommonly full for a man.

For a second, Lavinia imagined the devastation this smile and this mouth must have caused among the ladies of the ton before the gentleman took his honoured post and among the ladies of the court after he did.

‘I do hope,’ the first keeper of the robes remarked, ‘you are not finding yourself enraptured by Viscount Granville.’

‘Of course not.’ Lavinia finally looked at her, but she couldn’t quite summon enough indignation to infuse her voice with. ‘I didn’t even know his name and title before you told me.’

‘I doubt you have any need to know his Christian name in any case. It is unlikely your paths are going to cross that often. At least, I hope they won’t for the sake of your own safety.’

‘Is he a violent man?’

‘He is worse. He is a man without an earnest bone in his body as countless ladies who had been the recipients of his gallantry can attest. The ladies in question had their husbands’ names to protect them, not to mention their noble blood. You, Miss Dudley, do not.’

Lavinia recoiled almost physically. The first keeper of the robes was often guilty of petty cruelty, but lying was not among her habits. If what Mrs Schwellenberg said was true, Lord Granville was one of the most dangerous creatures to young women like her. A pretty-coloured viper, someone apt to drain one’s life and dignity away before leaving one as a disgraced husk and merrily moving along to another victim.

Lavinia wasn’t sure vipers drained their victims. She made a mental note to work on her metaphors. Her new life of service gave her very little time for actual writing, but that didn’t mean she could allow her skills to go to waste.

It was as though the viscount heard her thoughts, for as soon as the music had stopped, he stepped away from his group and walked in her direction. He couldn’t be genuinely interested in her company, could he? The sandy-haired viscount stopped when he reached the corner where Lavinia and Mrs Schwellenberg were standing.

At first, Lavinia still entertained some vain hope he wanted to strike up a conversation with the first keeper of the robes, a far more exalted lady than Lavinia herself was or would ever be. When a smile lit up his face like a touch of sunlight, it was Lavinia he was looking at.

‘I don’t believe I had the honour of being introduced to you. I beg you to forgive me.’ His voice was light as satin without a trace of any kind of grave regret. ‘I haven’t had the time to make many acquaintances. Serving His Majesty is not a sinecure.’

Neither is serving Her Majesty, Lavinia wanted to reply in this same easy, sparkling tone. His words loosened something in her, if only for a moment. That must have been how those women who followed every dictate of fashion and laced their waists in tightly felt when their stays were loosened.

But the first keeper of the robes was breathing over her shoulder, and the ballroom was filled with people with keen ears. So, Lavinia couldn’t say the truth or even hint at it. Instead, she schooled her face into an expression of formal politeness and replied, ‘I am sure it’s a great honour for your family.’

‘My father would have considered it a great honour indeed, had he still been with us.’

‘His Majesty is a father to us all,’ Mrs Schwellenberg intervened sharply. ‘And he has need of his sons, especially in times of trouble.’

Lavinia suspected all three of them knew that when she spoke of trouble it was not the war with France she meant. It was the battle raging inside King George’s own head, the battle where there could be no victors.

But no one speaks of such things in the middle of a glittering ballroom, guarded and warmed against the winter chill, on an occasion as awash with joy as a royal birthday. No one was supposed to.